LNG 101

Although it is currently the subject of much attention, LNG has been transported around the world since 1964

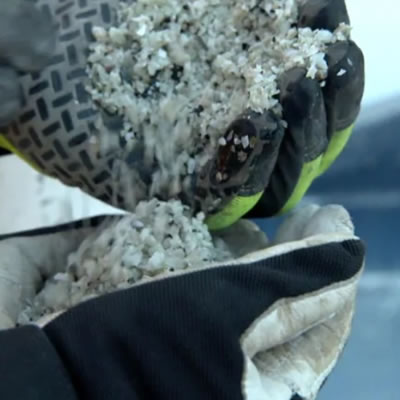

Between the Tilbury plant in Delta and Mt. Hayes on Vancouver Island, FortisBC stores 2.2 billion cubic feet of natural gas in case service is interrupted by weather. — Photo courtesy FortisBC

As British Columbia’s known natural gas reserves increase and both domestic and export opportunities become more viable for producers, questions about the basics of what liquefied natural gas (LNG) is and how it will affect the province’s future—economically and in terms of safety—are on everyone’s mind.

Although it is currently the subject of much attention, LNG has been transported around the world since 1964, covering 140,000 journeys, and without major incidents at port and at sea.

LNG is conventional natural gas brought to a liquefied state by cooling it. During the cooling process, it condenses by 600 times, facilitating its storage and transportation to global and domestic markets.

It is shipped via double-hulled carriers designed to handle LNG at its -162 C temperature; these carriers are accompanied and assisted by tugboats, and require trained and accredited pilots for berthing.

LNG is considered an environmentally safe energy supply compared with oil or other fossil fuels because it does not contain oxygen and therefore can’t burn or explode. LNG is odourless and colourless, and when poured it appears to be bubbling or “sparkling” and has a fog on its surface, which is simply the moisture in the air condensing out of it. In a spill situation, the substance would rise and dissipate.

Mark Grist, senior manager of business development at FortisBC, said the company is actively developing new energy products that customers will need in the future, including natural gas for transportation and renewable natural gas biomethane supplies.

As the province's largest energy provider, FortisBC serves approximately a million customers in 135 communities province-wide. It has run its Tilbury LNG plant in Delta since 1970 and also has the Mt. Hayes facility on Vancouver Island, located near Nanaimo. Collectively, the facilities store 2.2 billion cubic feet of LNG kept as an insurance policy in case of weather-related interruption to residential and commercial services.

In B.C., LNG’s supply chain starts in northeastern B.C. where conventional and non-conventional natural gas is pipelined to processing facilities, which remove the acid gas—carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulphide—to purify to sales gas specifications. It is sent to FortisBC's transmission lines where it is shipped to customers, including the company’s LNG plants. There, it arrives 95 to 96 per cent methane, 1 to 2 per cent ethane, and 0.5 per cent propane. The rest is contaminates such as carbon dioxide, residual hydrogen sulphide and mercaptan, which are removed.

Once purified, it is refrigerated using a mixed refrigerant process driven by electricity. After the gas is liquefied, it is stored in large tanks at atmospheric pressure or one PSI above atmospheric pressure. The tanks are double-walled, rendering them inherently safe in the event of a problem, as the second wall has enough containment to contain the LNG.

LNG vapour is flammable, but has tight flammability limits—a mixture of vapour and air more than 15 per cent or less than 5 per cent will not ignite.

“In addition to producing LNG and to back up all our customers, we are also developing a variety of end user markets for LNG,” said Grist. “LNG is not just for export to Asia to power power-generation facilities. It can also be used in a variety of useful domestic applications. The most exciting in my view is natural gas for transportation.”

Of particular interest are high-horsepower applications such as heavy-duty trucks, locomotives, ferries, marine vessels and mine haul trucks. The main benefit for the end user is cost—LNG saves 50 to 60 per cent of costs over diesel.

Provided the engine is properly designed for LNG, the substance provides equivalent performance while reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20 to 30 per cent on a wells to wheels basis, based on B.C. characteristics.

Its use also improves the quality of the airshed with reduced particulate emissions, and oxides of sulphur and nitrogen, which are the precursors of smog.

“The economic benefits of using LNG as a transportation fuel are a bit of a well-kept secret,” said Grist. “We sell LNG by the tanker truck out of our Delta facility and the price of that is less than 30 cents per diesel litre equivalent. Compare that to the rack price for diesel fuel here in Vancouver, which is presently about 88 cents per diesel litre, and you have a tremendous cost advantage there.”

Add in the savings on motor fuels and other taxes, and an operator that runs a fleet of vehicles can save millions.

FortisBC plans to invest in adding LNG production facilities to support the local market. Front-end engineering design is underway for a major plant located at Tilbury. The new facility will expand the scale of the Delta plant but still remain significantly smaller than export facilities planned for Kitimat and Prince Rupert.

“The development of the export LNG plants is being driven by differential pricing between markets in Asia and the domestic North American market,” said Grist. “Sales of B.C. LNG into Asia are going to produce higher netbacks for the producers than sales into the domestic market.”

Once those larger facilities are built and have the capability to ship to Asia, most are expected to serve the higher paying export market, leaving an important need for smaller plants willing to provide for the domestic market.

“We believe the export opportunity makes sense from a B.C. resource development perspective, especially since the supply base has increased from 52 trillion cubic feet of conventional resources to 1,200 trillion cubic feet of unconventional resources to add to that 52 trillion,” he said. “The province is blessed with huge supplies of natural gas and it does make sense to develop that gas for both domestic and export markets.”